BEING OF SERVICE

Victor Power, Driver

My dad spent one night in the rehabilitation home and said, “If you don’t get me out of here, I’ll crawl out on my hands and knees.” He was a feisty man. And at 6’2”, 220 pounds when he was healthy, I never thought he’d die.

Ed Power was a Shriner and was involved with the Elks. He said the hardest thing he ever did was to memorize the speech he gave when he received the Grand Poobah Fez. He used to cook for the Elks Lodge in Clearlake, California—that was for roughly 600 people with only a few people helping him prep. He loved to fish, and had 200 pounds of fish in his freezer at any given time. He was my coach in little league, and he played a mean golf game. And that was all in his off time.

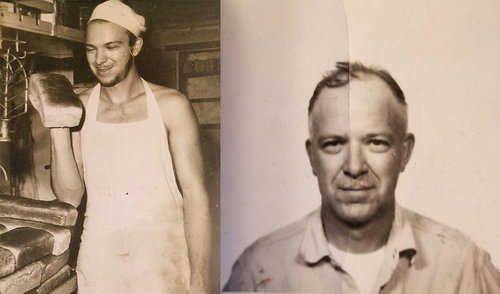

Ed Power in the Coast Guard in the 1930s and at McClellan Air Force Base in the early 1960s

Ed Power in the Coast Guard in the 1930s and at McClellan Air Force Base in the early 1960s

He was as active professionally as he was in service. He worked at McClellan Air Force Base from 1956 until the 1970s, and did a year of civil service in Vietnam. Then after he retired, his home in Clearlake got flooded, so he and my mom decided to move to Apache Junction, AZ.

He was diagnosed with ALS in 1996. It was hard to see him go down like that—his muscles deteriorating every day. I’d go visit him in Arizona as much as possible. Finally, we had to put him in hospice; my Mom just couldn’t take care of him anymore. We tried a rehab home first, but it wasn’t a good fit for the dignity he still carried himself with. We eventually found a place that we all liked—a place that felt like home. He was there for three to four months before I got the call.

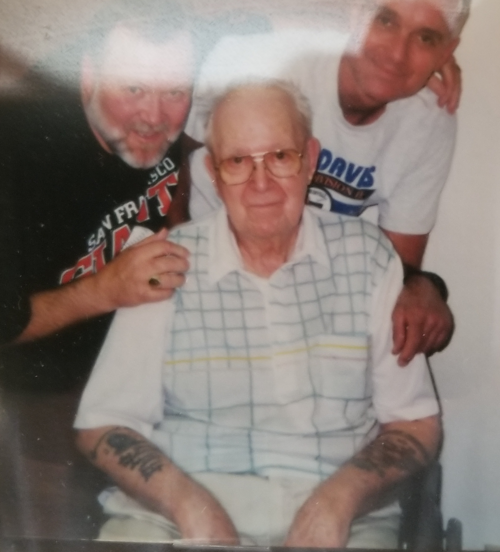

Ed Power in 1991 with me and my brother

Ed Power in 1991 with me and my brother

He had passed quietly in his bed, covered only by a single white sheet, one leg uncovered. My mom had been by his side for two days and nights without sleep. Finally, she watched the blood move up and then back down his leg under his now translucent, paper thin skin. In an instant, the blood stopped moving, and that was it. She said it was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. He was 79 years old.

I got back on a plane the next day to go back to Arizona. I was hugging my mom when the phone rang. It was my aunt on my dad’s side, Aunt Daisy. I had never seen or talked to her in my life. She had called out of the blue to see how her brother was doing. That was the first and last time I ever spoke to her.

Dad wanted to be cremated. The hospice people had prepared everything before we arrived so we didn’t have to worry about anything. I told them I wanted to see the process. I wanted to know everything was being done right.

My dad was laid out in his favorite golf clothes—green trousers with a pink and white checked shirt. After the cremation, my brother, Mom, and I shared the notes we wrote to him. We cussed him out. We went through all the emotions. Then we walked outside into the sunshine and watched the cars passing by. Life just goes on.

The day after he passed away, I picked up the phone to call him. Then I realized he wasn’t there anymore.

I’m 71 and retired now, but I’ve been working as a driver for MCI for three years. It’s important for me to continue to be of service—just like my dad was. I know this job has meaning because I saw how important this piece of the healthcare puzzle was when my dad got sick. I take pride in my work with Medical Couriers because I’m helping people like my dad everyday.